My father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and I'm going to stay right here and have a part of it, just like you. And no facist-minded people like you will drive me away from it. Is that clear ? Paul Robeson 1956

If I had to say what one person who I knew had made the biggest impact on my life, I would have to say Dr,John Henrik Clarke. For he made you think not only who you were but what you might become .And this had a profound effect on me, for he had the greatest memory and recall of book's and events of anyone I ever known. Dr Clarke was a father to everyone and was our esteemed GRIOT here in Black America. I'm sure in his past life he was a benevolent African King. He was also the person that inspired Malcolm to be the Pan Africanist that he became and taught Malcolm what it was to be a proud African. It was Dr, Clarke that helped Malcolm with the constitution to Malcolm's new Organization of Afro-American Unity. The first person to use the term African American was Malcolm and I'm sure Dr, Clarke had a lot to do with it.

Dr, Clarke meant a lot to quite a few people, and even in his passing still has a effect on so many people and I like to present a piece of Dr, Clarke's work called "Can African's Save Themselves ?" I'm sure you'll enjoy it and I like to expose people who have never heard of or knew of this GREAT MAN that they missed someone who I feel was a prophet in his own right. I'm sure the people who knew him would agree with my assessment. More then anyone that I knew Dr, Clarke was the total Pan Africanist and asked questions of us that made us look inside ourselves and want to be what he asked us to be. And that was a people who give this world a new Civilization since we gave the world the first civilization; he knew what we could do when we thought other wise. So here is my tribute to you Dr, John Henrik Clarke and Thank You, for being the light in a dark world.

Can African People Save Themselves ?

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom,

it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of

incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was

the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us,

we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going

direct the other wayin short, the period was so far like the present period,

that some of its nosiest authorities insisted on being received, for good or

for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

THE ABOVE QUOTE IS APPLICABLE to the African world of today with some slight

modifications. African people can have a Golden Age or another Age of Continued

Despair, depending on how they view themselves in relationship to the totality

of history and its ironies. The cruelest thing slavery and colonialism did to

the Africans was to destroy their memory of what they were before foreign

contact. Africans have not dealt forthrightly with invaders, slave traders and

colonialists, who came among African people as guests and stayed as conquerors.

The strongest thing about African people is their respect for the humanity of

other people and the hospitality they have shown to strangers. In most cases,

Europeans and Western Asians have come into African societies as guests and

stayed as conquerors. Africans have never had a strong armed force. They

assumed that they did not need one because they had no intention of conquering

other people.

Too many times in the past and in the present Africans have had a parochial

view of Africa. There is a need now to look not only at

the Africans in Africa, but also at how they relate to

that vast number of Africans who live outside of Africa.

Properly counted, considering the large number of Africans in the Caribbean

Islands, North and South

America, and the millions of people of African descent in India

and in the Pacific, Africans may number at least a billion people on the face

of the earth. Africa is the last mineral and geographic

reserve in the world. Africa has been and still is the

grand prize that non-Africans have always wanted to conquer.

Because Africa is the worlds richest continent a great

deal of the economic strength of the Western world and parts of Asia

is built on what is taken out of Africa. The continent

has things that other people want, think they cant do without, and dont want

to pay for. Africa is the pawn in a world power game

that the Africans have not learned how to play. I emphasized repeatedly that Africa

has been under siege for more than 3,000 years, and this condition did not

change with the superficial end of colonialism and an independence explosion

that had more ceremony than substance. In most African countries the condition

of the average African person has not changed one iota with the coming of

flag independence. All too often Africans fighting for the liberation of AfricaAfrica

before they strategically planned how they were going to do it. A case in point

is South Africans in the international rhetoric against apartheid. Apartheid is

not the main issue in South Africa,

bad as it is. If the whites in South Africa

eliminated apartheid tomorrow, the Africans would still be in difficulty

because they would have no economic power and their land would still be in the

hands of foreigners.

Land is the basis of nation. There is no way to build a strong independent

nation when most of the land is being controlled by foreigners who also

determine the economic status of the nation. Africans need seriously to study

their conquerors and their respective temperaments. Neither the Europeans nor

the Arabs came to Africa to share power with any

African. They both came as guests and stayed as conquerors.

There is a need now to study, at least briefly, the more than 3,000 years when Africa

was under siege, and under pressure from foreigners who had no understanding or

respect for African religions or customs. The Hebrew entry into Africa

occurred in the 1700s B.C. They came into Africa

escaping famine in western Asia. They were treated as

guests by the Africans. In 1675 B.C. Africa was invaded

from western Asia by warriors referred to as Hyksos, or

Shepherd Kings. The Hebrews were acquainted with these warriors because some of

them came from the area of their migration. Therefore many of the Hebrews

became collaborators, clerks and administrators for these invaders, working against

the interests of the Africans who had befriended them. When after nearly 200

years of this occupation the Africans organized a force large enough to drive

out the invaders, they began to ask some questions about the Hebrews who had

been their collaborators. The story of Hebrew slavery in Africa

is just that, a story. There is no proof of this matter in Egyptian

literature or in western Asian literature.

Outside of the Bible there is no proof of probably the best-known incident in

human history, the Exodus. Both the slavery of the Jews in Egypt

and the Exodus could be Jewish folklore and nothing more. After this period in

history, Nile Valley

civilization and Africa in general enjoyed almost a

thousand years of peace without antagonism from foreign armies. In 666 B.C. Africa

was invaded again by people then referred to as Assyrians. All these wars were

assaults on African culture and the different African ways of life. In the year

550 B.C. AfricaIran.

These invaders were so brutal that some Africans cried out, Oh God, if you

cannot send me a liberator, send me a conqueror who will show some mercy! The

next conqueror was a young Macedonian referred to in history as Alexander the Great.

The year was 332 B.C.

The Romans invaded North Africa and destroyed the city

of Carthage from 264-146 B.C. The

greater portion of the Roman Empire rose in Africa

and fell in Africa. If African people are to save

themselves, they must first see themselves in relationship to the total history

of mankind. They must also understand the insecurity of their invaders that

caused them to downgrade the importance of African people in history in order

to aggrandize themselves at Africas expense.

This subject is monumental; it is not parochial, not local at all. It breaks

out of accustomed mold. We have not asked and answered the question of where we

African people are within the context of world history. We see history

unfolding around us, and many times we develop a complex, assuming that we are

not the makers of history. Something has divided us between the period when we

made history and the period when history was made at our expense.

We were once not only the makers of history but we were the makers of the world

of our day, and this lasted for thousands of years. One must be reminded that

over half of human history was over before anyone else knew that a European was

in the world. African people were in the world and had been there for thousands

of years. We were not sitting around idly, either. Let me put a timeline on it

so you can understand this statement.

As I have noted elsewhere, Africa had existed over 3000

years intact before the first invaders (1675 B.C.); the first European invaders

came in 332 B.C. The first trouble came from western Asia.

That trouble was persistent and set Africa up for the

European invasion under Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. Then he, like all

Europeans (although he was more merciful than most and showed more

understanding than most), began to misinterpret African people and their place

in the history of the world.

We cannot save ourselves and decide where we are going until we understand

where we have been and where we are. With history unfolding before us, weve

got to become astute in asking and answering the question: Where are we in

relationship to what we are seeing right now?

Lets look at some current events and analyze them to see how the Africans

living outside of Africa relate to these current events.

Where are we in relationship to Panama?

How do we relate to it at all? The head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the

supreme commander of the United States Forces during the invasion was

superficially a person of African descent. I mean this both figuratively and

literally. He participated with glee in the military encounter. He did not

understand nor was it called to his attention that he is a Jamaican and his

people died in the thousands while digging that canal. See, when you dont know

your own history look at the traps you fall into. You become so patriotic. It

was Jamaicans more than anyone else because they had unemployed people, so they

sent more labor. They labored on that canal for years, Jamaicans, Trinidadians,

Barbadians, but mainly Jamaicans. When they demanded a raise to ten cents an

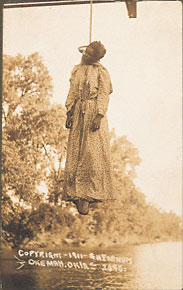

hour, they were lynched.

But we act as though we have no vested interest in the canal, that its

somebody elses show.

Lets play the historical record back 500 years. Lets go back to the opening

up of the Americas,

back to the 1400s, back to Balboa, the Spanish conquistadors, to the discovery

of that area when it was called the Isthmus of Darien. African road builders

built a road in what was going to become Panama.

They could handle so-called Indian labor, indigenous Americans, without the

lash. How could Africans recruit the indigenous population referred to as

Indian without the lash, get them to work without mutilating them and

humiliating them and whites could not? The African humanity in the recruitment

of labor was different. All of this is forgotten history.

The minute we heard about Panama

we should have asked, Well, what role did we play? How do we relate to all of

this? Look at the contradiction of a Jamaican being Chief of Staff. Im not

worrying about whether hes entitled to be it; hes probably more than

entitled; thats not the issue. But look at the contradiction. His people dug

the ditch and died in the thousands. One of the main reasons his people dug the

ditch while whites died of yellow fever in the thousands was because something

the Africans believe proved to be true: The mosquito has a taste for white meat.

Let me digress with a relevant personal anecdote. While traveling from Ghana

to Togo the bus

broke down at the border checkpoint. I didnt know till later that the bus driver

gets paid according to the length of time it takes to make the trip; so it

conveniently broke down at the border checkpoint. Then we had to spend the

night there with no hotels, no rest houses, nothing. So, we slept on the beach.

A fellow said, Mr. Clarke, if you sleep near fresh water with your head lying

in the direction of the wind, the mosquito is not going to touch you because

the wind will take your scent away. Not only do Europeans lie the wrong way,

they smell the wrong way, and attract the mosquitoes.

So, no matter what you think of your smell, its in your favor in relationship

to the mosquito. Therefore, while some blacks did die of yellow fever, most of

them survived to dig that ditch. Now you can see how we relate to everything.

Nothing happened in Panama

that we dont relate to in some way. We cant save ourselves until we become

astute at identifying our relationship to everything in the world, because we

do relate to everything in the world.

Now lets deal with the so-called dictator, Noriega. He went to American

military school. He is a light-skinned one of us. That didnt make it any

better for him; they called him a nigger. He didnt associate with the whites

for a while. When they found out that they could use him, they let him pass for

white. Then they let him engage in skullduggery until he engaged enough to have

as much on them as they had on him. They dont want to try him; they want to

kill him before he can talk.

Now we can understand that one of us who is a fraction will suffer the same as

the blackest of the blacks once we fail to play a power game. My point is that

to understand our history (past, present and probably what it will be in the

future) we need to know more than our history. We need to look holistically at

the world. This is what we have not been doing. Right now we should be getting

ready to debunk all of the celebration around the 500 year anniversary of the

alleged discovery of America

by Christopher Columbus. We should be getting ready now to prove (and we can

prove it) that he discovered absolutely nothing. He never set foot on North

America or South America. He stumbled up on

some islands, and he depopulated every one of them. Everywhere he went he

destroyed the people.

We should have conferences, entire conferences, devoted to one item:

revelations of Father Bartholomew de Las Casas, the first historian of the New

World. We need to read his work and talk about it for three days,

and not mix it with a thousand other things. It was Father de Las Casas whom Christopher

Columbus went to (when he saw the so-called Indians dying wholesale) in order

to get an increase in the African slave trade to save the so-called soul of the

Indians. When the Pope sent commissioners to look into the disappearance of the

Indians, many islands didnt even have one left. They were dying wholesale of

malaria and mutilation, of brooding themselves to death.

Now you have to look at the culture of a one-dimensional people. Im not

dealing with good or bad; Im dealing with culture and how sometimes such

people can get into a culture trap of their own design. We are in such a trap

because we believe that the white man was telling the truth when he gave us

Christianity. We didnt go beyond what he was saying and look at the

spirituality we produced and gave the world before Christianity. We dare not

read about it; we dare not think about it. We dare not examine the Conference

at Nicaea (325 A.D.) where the

fakery that is now Christianity was foisted upon the world, and the reality and

spirituality which we gave the world got lost.

Im not saying anybody should walk the world godless or spiritless. Im not

saying leave any church; stay in them. Make them infuse spirituality in

religion. We have a revolutionary dynamic. but without spirituality we are

wasting our time. This is why Im against all the millionaire phonies,

imitating black Baptist preachers, like Jimmy Swaggart and others who have the

spirit of a dog. Theyve taken something from us and they are disgracing it. If

you understand what is happening before you, you will understand what youve

got to do.

Now lets look at what is happening in Europe. It is not

an argument between communism and capitalism; it is a difference of opinion on

the methodology of European control of the world. Europeans have decided that

they would control the world, be it communist, capitalist, socialist or

fascist.

There are certain Oriental races who have decided that they will help them, but

we think that once we deal with our white enemy we have no other enemy. We are

dead wrong. People want power by any means necessary, and they will take it

from any person on this earth who has not learned how to use it properly. And

we African people have not learned to use it properly, not even how to protect

our own community.

If were going to save ourselves, there is something which I have called the

essential selfishness of survival which we are going to have to start

practicing. There are some blacks who will say this is black racism. I say it

is not. It is survival, but if someone wants to classify it as black racism, so

be it.

I think we should own every single house in the famous ethnic community

called Harlem, control every single house in this

community; control every single store in this community; employ people in the

community running these things properly; have our own social agencies;

eliminate homelessness and put people to work renovating houses in this

community. If we did this and walked upright, began to fix our own shoes, had

small factories, independent schools, good day nurseries, good child care, a

national theater with its headquarters in this communityif we did all of that,

we would be practicing nation building. We will have at last understood what

Booker T. Washington was saying, what W.E.B. DUBOiS was saying, what Marcus

Garvey was saying, and what Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X were saying. I dont

separate one from the others.

I am not endorsing Islam. (I think religion without spirituality is a waste of

time, anyway. Nor am I looking for a new one.) I would not even name Elijah

Muhammad except for the fact that he did make a contribution toward

nation-consciousness. In nation-consciousness you can make your own religion.

You can go to his or you can make another one or choose another one. The laws

of nation-consciousness are the laws of responsibility, and we are not going to

save ourselves until we are conscious of nation-responsibility and

nation-building. We are not going to save ourselves as individuals; were going

to do it as a collective. To do it as a collective, were going to have to be

bold enough (even if we have to break our own hearts) to find out where we went

wrong.

Throughout history we have been politically a naive people. We have trusted the

wrong people; we have bought false goods from fake salesmen. We have bought

things of a synthetic nature, not knowing that we had real things at home all

the time. We have forgotten the facts because we have not studied our history

seriously and recognized that before there was a Europe

we built enduring civilizations that lasted thousands of years without a jail

system. We had family structures that were so tight, and the family was

structured in such a way, that crime and punishment were taken care of within

the family and jails were not needed.

There was no word in the Africans languages that meant divorce. Because each

party had a support system, the uncles, the

fathers, the mothers, all there

together. Then foreigners declared war on this support system. Throughout our

history we have always been (and still are, in spite of the contradictions) the

worlds richest people: rich in culture, rich in minerals, rich in ideas, rich

in imagination. We have not used these great riches to save ourselves.

White musicians can do a good imitation of our music, but they could not do an

exact imitation if their life depended on it. Benny Goodman played one

imitation of our music over and over and over, but he didnt innovate because

he didnt know how. He learned a form and played the form over and over. I

remembered Charlie Parker playing Aint She Sweet. I listened to him three

nights straight, and he played the song a different way each night and yet he

still was playing Aint She Sweet. He played it according to his mood; he

wasnt in the same mood each night, so he didnt play the same way each night.

Some nights it sounded better than others, but he didnt kill the tune of the

song.

Figuratively speaking we Africans have been put on the world stage without a

script, and the audience has said to us, Act or well kill you. And we have

acted; thats the nature of our survival. We have learned something about

survival that has eluded other people. We have not used what we have learned to

continue to survive. We have become prisoners to forms other people have

created without using our imagination to survive. If we had used our

imagination, we could have rebuilt every boarded-up house in every metropolitan

community where we live in the United States.

Were good carpenters, imaginative planners, and great decorators, because we

use color in situations so well. The question is, why havent we used our

cultural gift to save ourselves?

Lets look beyond the United States.

Lets look at the Caribbean Federation (a great heartbreak to me). Lets look

at the Civil Rights movement (another heartbreak), and lets look at the

failure of the African Independence Explosionthe greatest of all the

heartbreaks because that could have saved the two of us. All three of them

failed because instead of using our imagination, we were using forms developed

by someone else, not knowing that the slave master and the colonial master

created nothing that we can use to save ourselves because his form was to keep

him in control of us. When we use this form to control our own people, our

situation is merely changing faces. We change our condition without changing

our position. We have to understand the nature of the position in relationship

to the condition.

There is a need now to examine the Caribbean concept of

union and federation. The idea of Pan-Africanism was formulated by the Caribbean

mind. How is it that the three great Pan-Africanists came from Trinidad:

H. Sylvester Williams, George Padmore and C.L.R. James? They could never unify Trinidad.

The great federalists mostly came from Jamaica.

The great internationalists came mostly from the Virgin Islands, men like

Edward Wilmot Blyden and Hubert Harrison, but mainly Blyden, who tried to build

a three-way bridge between African-Americans, the Caribbeans and Africa.

Today, in no part of the Caribbean Islands,

does one find any nationalism of consequence.

Even the Rastas are confused. Many of them are actually rascals. Some are

beachcombers, roaming the beaches of the Caribbean,

serving the unfulfilled physical needs of female tourists. Is this on their

road to Africa? It is at best a side road. Thus, theres

some confusion, even by those who claim Africa in

purity. And anybody who claims Haile Selassie as the incarnation of God on this

earth is confused about the history of Haile Selassie.

I like the idea of the Rastas. I wish some Rastas werent rascals. I wish there

were something in the Caribbean Islands

of pure Black Nationalism, because theyve got something we dont have here

theyve got a majority. Theyve got something else we dont have, a special

kind of revolutionary heritage based on being a majority. Their slave revolts

were the most successful of the slave revolts outside of Africa.

They have forgotten their revolutionary heritage and become too dependent.

Their slave revolts were successful because they had an African culture

continuity. Our cultural continuity in this country was broken, almost

destroyed, and yet we maintained a large degree of that cultural continuity.

Come to Jamaica!

Everybody in Jamaica

wants to be something except an African person. Theyre willing to tell you

about their Dutch uncles, Scottish grandfathers, etc. I have not found one who

will say boldly, I am an African person.

At a conference on Marcus Garvey in Jamaica

in 1987, I raised a question: Where would Marcus Garvey be safe in the Caribbean

Islands? Where would he be safe in

the world if, indeed, he were alive walking around? Where would he be safer If

he were in Jamaica,

I believe some politically deranged person would stone him to death; he failed

twice in Jamaica.

Hes dead now; theyll make him a hero, bury him at Kings Park. Everybody

says, Marcus Garveys buried out there. They emphasize that hes buried

there. When youre dead, you cant hurt anybody. Anybody who would elect Edward

Seaga (a Lebanese con man from Boston)

as their Prime Minister has placed their African loyalty into question.

There may be some hope. I havent found it. Yet, if the Caribbean

Islands are ever to be the seats of

the rallying cry for the return to Africa, it will begin

in Jamaica. It

has the resource; it has the intellectual personnel; it has the technical

personnel. Just as, if Nigeria

becomes a truly African nation (and not a den of thieves), it can change all of

Africa. Half of the lawyers, technicians, the

African-trained engineers, school teachers and qualified professors in Africa

are Nigerians. Nigeria

could turn Africa around, if it would, but it would have

to work as a collective and not as individuals.

Lets look at what we call the Civil Rights movement in the United

States and why this failed to be a vehicle

that we could use to save ourselves. Lets see if we can show you that when you

do not understand the nature of the history behind an event, youre going to

misinterpret the event, misuse the event and misuse yourself in relation to the

event. These young people, brilliant, beautiful, and brave, got the illusion

that they were making a revolution such as had never appeared before among

their own people. They were totally ignorant of the early nineteenth century

black revolution of the black freedmen in New England

under Frederick Douglass; of the newspapers published by that group (The

Anglo-American, Douglass North Star, Freedoms Journal). They were ignorant to

the relation of the brilliant Caribbean minds to that

movement, ignorant of the great contribution of the Barbadian, Prince Hall, who

founded our Masons (and didnt call it Masons; Black Masons or anything like

that). He called it the African Lodge.

Why were we closer to Africa then than we are now? Why

did we have a romance with the word Africa then and

were avoiding it now? Why do we want to be something else now, when we were

comfortable being African then? When we lose our African connection, we lose our

world connection. When we disconnect ourselves from Africa,

we cease to be a world people. It is the African connection that makes us an

important people of the world. Without the African connection, we are a

disjointed people (just hung out), begging for entry into somebody elses

house.

As an African people, weve got a big house12,000,000 square miles, full

of riches. And people are begging to enter our house to enjoy its riches. We

are on the outside, not developing the talent to master those riches and

exploit them for the benefit of all African people of the world, or anybody

other than European investors. If we stop talking about apartheid long enough,

we would realize that the real issue in South

Africa is not apartheid. It is European

control over the mineral wealth of the world, with the headquarters of that

control being in South Africa.

Most of the countries that control the mineral wealth of the world are in

support of South Africa.

In Cheikh Anta Diops little book on Africa (written over

ten years ago), Black Africa: The Economic and Cultural

Basis for a Federated State,

he outlined exactly how the mineral wealth of Africa was

taken. He tells us exactly what were going to have to do to take it back and

to preserve it for African generations still unborn.

Cheikh Anta Diops work, Civilization or Barbarism, his fifth and last book,

has not been published in English. I have not met ten people who have seriously

read his work. In this book, written before his untimely death (when a man is

great, any death is untimely, even if he dies at 102), he takes off the gloves.

He doesnt say maybe anymore; he doesnt hedge anymore; he doesnt say the

information points or it indicates. This is his final confirmation of the

truth of African history and how African history relates to world history. We

know for the first time our place in the history of the world.

My main point is that we have not heard our greatest messengers, and we

interpreted as a fight a lot of things in our life which were not fights.

Booker T. Washingtons message was one of self-reliance, and we condemn him as

being an Uncle Tom because he did not take public stands on many things. Yet,

Booker T. Washington could have scratched his head when it wasnt itching,

could have shuffled when there was nothing funny; he did achieve something we

need to respect him for. He did keep Tuskegee

open; he did train a generation of people; he did develop an education system

that was good then and is good now.

Had we followed that system and paid respect to him, you would never see a

white plumber working in a black neighborhood, because we would have our own.

If you live in a brick house, you should have a brickyard; if you wear leather

shoes, tan your own leather and make them. Kids used to walk to Tuskegee

through three states; they didnt have any money. They would walk their way to

school barefoot. Booker T. Washington used this as an opportunity to start a

shoe repair shop and later developed courses for designing shoes. For years most

of the blacks trained in design of orthopedic shoeswere trained at Tuskegee.

Its all gone now; its a liberal arts school (as though we dont have enough

of those). We need more good technical training schools, schools where a man or

woman will be trained to be a plumber, trained to lay tiles.

A good plumber makes more money than a good college professor. If you can lay

tile in a bathroom properly, you make more than a college president. Theres

nothing wrong with using your hands and your brain at the same time. If you put

those two things together with skill, you go home with nice money. We have

forgotten this in the smugness of looking at Hollywood

and at the soap operas (the most unreal thing in existence, even unreal to the

people who created them).

My point is that when we look at the Independence Explosion that began in Africa

in 1957 (with the independence of Ghana),

the real genesis of the explosion was a hundred years before. Throughout the

whole of the nineteenth century most Africans did not negotiate anything with

the Europeans. They did not go to Whitehall;

they did not go to Europe and be dazzled with the

chandeliers; the smiling ladies and the champagne. They picked up their spears

and their shields and went to the battlefield. And they out-generaled some of

the finest soldiers of Europe.

There is a good record of it in Edward Rouxs book, Time Longer Than Rope.

There is also a record left by the young Winston Churchill, one of the greatest

war reporters since Caesar came home from Gaul, about

the Sudan, The

River War. The people that the Africans opposed and defeated wrote it down. We

should read the record of the last of the Ashanti

wars led by a woman, Yaa Asantewa, ably supported by men. This was the time of

the siege of Kumasi, the great

drama of Kumasi. Any history of Ghana

includes the story of that war and this brilliant woman.

We keep comparing ourselves with Europeans, but we are not Europeans in

temperament. No European would have followed a woman into a war for nine

months, giving no quarter and asking none. She had that war won until a great

contradiction in history appeared: the famous West Indian Regiment, that she

thought was friendly.

She told her men, in effect: Lay down your guns and go out and greet our

brothers; theyve come to help us at last. Those brothers were in the pay of

the British and had come to do them inand they did.

We should celebrate Yaa Asantewas war. It shows that we have not looked at

women in the same way as the European. Even in courtship, when we take the same

approach as the European, we are dead wrong. When we take the same general

attitude toward women as the European, we are dead wrong.

The European fears women; if he enslaves ours, he enslaves his, too. The only

difference, many times, is that the European womans auction block,

figuratively, is air-conditioned; but shes on the auction block, too.

When we look at this African Independence Explosion, we must take into

consideration that not one African nation came to power using a conventional

African structure of government. Every one used an imitation of parliamentary

procedure taken from Europe. Its like wearing a coat

that wasnt designed for your body and will never fit. The tailor has never

seen your body, and, therefore, cannot cut a coat to suit it. This is something

you have to do yourself, because you cant wear a tight-fitting coat. You need

another kind of coat, politically and figuratively speaking. Africa

will never succeed using European parliamentary techniques.

It will never succeed using Christianity or democracy as designed by the

European, because the Europeans theorized these concepts, while, in most cases,

the Africans lived out these concepts without dogma or without making them into

rationales for the conquest of other peoples. The African never used the word

democracy.

He never used the word, yet he had more democracy than the European ever dared

to practice. This is where some lawyers need to study the African customary

court system. When the late Pauli Murray, who was a brilliant lawyer, went to Africa,

I asked her, Why dont you study the customary court system in Africa?

She never got around to it, but had she studied it, she would have learned that

it is democratic to the point of being cumbersome. For example, the accused can

examine everybody in the court, including the judge. The case is not closed

until the accused calls his last witness, and generally the last character

witness is his wife, who will bear witness to his good character and whether he

takes care of his family. If that fails to convince, hes guilty as hell.

It is a system that takes the mans total humanity into consideration. Now will

we throw away all of that for a European system? Where were you on the night

of June 13th? Thats not the issue; besides I cant remember. In an African

court the issue is whether you have violated the customary laws that govern the

society and having done so, whether you have endangered the whole society. If

you have endangered the whole society, then the entire society has a right to

call for your punishment. The judge of the case (once you are proven guilty)

asks you what sentence you think needs to be passed upon you now that you are

proven guilty.

In most cases, the guilty party announces a sentence for himself more harsh

than the court normally would put upon him. He participates both in his

innocence and in his guilt. This is democracy to the point of being retarding.

This kind of trial would last too long in America;

but the spirit of what the Africans are doing is worth preserving. In Botswana,

among the Bamanwaita people, where the court is called the Kahatla, you bring

your stool, your lunch, fresh water and diapers for the children. You sit under

a tree. You might come back in three days and find the trial is still going on.

We must rescue these old values, even if we update them, and prune away the

excess time involved (because we have to move faster now). We must talk to each

other, as we never did before.

When I was growing upbecause there was no such thing as illegitimacyyou

didnt turn a girl out just because she had a child out of wedlock. The ladies

in the community did gather around her and talk to her and let her know about

the danger of this kind of thing, and that it wasnt exactly the right kind of

thing to do. The men would gather around the man and want to know, Inasmuch as

youre not going to marry this girl, what are you going to do towards her

support?

Today, men are impregnating ladies and telling people, None of your business,

after all she should have kept her dress down. Girls have to learn how to

check people out before they favor them, and if theyre not dependable, not

favor them. Youre not going to die. You can go a long ways through life

without it; he aint going to die either. Some things can wait until you make a

proper selection of someone who you can depend on or believe in.

We need to concentrate on the quality of people we bring into the world.

Theres no point bringing someone into the world whos going to be a burden to

the society. We want everybody to be a contributor. To be a contributor, a

child needs more than mothering; it needs fathering, too. A child needs

socialization. If a child is without a father, he shouldnt be without the male

image in his life. If we are indeed going to save ourselves, we have to find

out not only what we have done wrong, but the number of people among us that we

have failed to make accountable to us. Everyone who calls himself or herself a

leader must be accountable to us. If they are too sensitive to be accountable

to us, then they dont go forth and call themselves a leader. Let us deny them.

Somewhere along the way all of us, in our fascination for foreign toys,

political and otherwise, reach the fork in the road. We have seen many roads

leading in many directions, and we read the signboards wrong. We went down

roads that did not lead us home. We have to go back to the fork in the road and

read those signboards again. We have to find a signboard that reads: Unity,

African World Federation, Pan-Africanism, African Solidarity. When we see that

on the board (the unification of all African people throughout the world, the

self- interest of African people first, black and black unity, meaning more

than black and white unity), after we go back to the fork in the road (meaning

we might have to go back before we can go forward) we may have to recheck

ourselves.

We might have to go back and make a principled decision. We might have to build

great industries; we might have to start with our underwear. The reason I say

start with underwear is because no one is looking at it. If we get our seams

wrong, weve got time to get it straight. Then we go to our shoes and our

suits. And we learn something that is basic to the re-emergence of modem Japan.

There are two things the Japanese would not let their conqueror take from them:

their self-confidence and their image of God as they conceived Him to be.

In slavery and in colonialism African people lost their self-confidence. You

cannot worship a white spiritual image of authority on the weekend, beg the

same image for a job the rest of the week and give full respect to the black

father, as the authority image, in the home. You cannot turn viciously on

yourself because you do not resemble that white image; you cannot look at that

same image as the epitome of everything good and look at the image staring at

you from the mirror as the image of everything bad. Psychologically, you cannot

save yourself until you love yourself. And you begin with the mirror. You stand

in front of the mirror until you like whats staring back at you. You speak to

the person staring back at you and say, You and I will start a revolution that

will change the world. We will start our revolution right now. I often say that

this is tomorrows work, and the time to start tomorrows work is today.

The International Congress for African Studies was held in Kinshasha,

Zaire from December 12 to 16, 1976. The main

theme of this conference was African dependency and its remedy. The conferees

talked about the subject for days without coming directly to the point or

asking the right questions, such as, Who progranimed African people into

foreign dependency, and how will they overcome this dependency in their

immediate lifetime? As one of the conferees, I called attention to the

groundbreaking and useful work on the subject done by Cheikh Anta Diop,

especially in his book, Africa, The Politics of a Federated

State. Part of my brief

intervention was as follows:

The theme of the congress, The Dependence of Africa and the ways of Remedying

Situation, has long historical roots and many dimensions and we have not

touched on all of them. I think most of us know that our papers and our

deliberations have not done full justice to the theme of this congress. At best

we have located the surface of the theme and scratched it all too lightly. We

have given many answers without asking the right questions. Who is to blame for

the dependence of Africa, and who is responsible for

finding a remedy? Most of us do not seem to be aware of the fact that African

thinkers have already asked the question and thought out some answers that are

worth serious consideration.

In 1960, Presence Africaine in Paris

published a work by the Senegalese historian, Cheik Anta Diop, Black Africa:

The Economic and Cultural Bases of a Federated

State. This book, first published

nearly two decades ago, dealt with the theme of this Congress. With all due

respects to our papers, and deliberations this week, Professor Diop, in my opinion, brought more to

the subject than our combined efforts. In the English edition of the same book,

recently published in the United States,

he brought his information up to date by first dealing with the Energy crisis,

now prevailing in Africa. He stated:

The days of the nineteenth century dwarf states are gone, our main security

and development problems can be solved only on a continental scale and

preferably within a federal framework before it is too late.

He calls attention to the drain of this nations energy by the major Western

powers in the following statement in his book;

Belgian-American interests preparing for the political instability that would

prevail in the colonies following World War II, working at maximum rate and

beyond, mined all the uranium of the then Belgian Congo in less than ten years

and stockpiled it at Oolen in Belgium. The Shinkolobwe mines in Zaire

today are emptied having supplied the major part of the uranium that went into

the Nagasaki and Hiroshima

bombs. Until 1952, Zaire

was the worlds leading uranium producer; now it ranks sixteenth in reserves

and has ceased to be counted among the producers. This one example shows how

fast our continent can have its nonrenewable treasures sucked away while we

sleep.

Professor Diops book is about all the things that we have been talking about

here this last week. The origins of African dependence and what can be done

about it. His approach is Pan-Africanist and Socialist.

The African-American historian, William Leo Hansberry wrote a shorter work on

this subject called Africa, Worlds Richest Continent Professor Hansberry calls

attention to the fact that the agricultural and hydro-electric potential of

Africa is the greatest in all the world. His findings provoke the question: If

Africa is so rich, why are most African people so poor? Who is managing the

riches of Africa? The Guyanian writer, Walter

Rodney, wrote a history of the origin and growth of this dilemma in his book,

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.

The essence of the point that I have been trying to get across is: The problem

of African dependency and the search for a remedy is not new. It is part of a

crisis that started in the fifteenth and sixteenth century, with the second

rise of Europe, the development of the slave trade and

the colonial system that followed it.

The dilemma is both topical and historical. This dilemma will not be resolved

until all Africa is completely liberated and freed from

dependency.

This is not the problem only of the Africans who live in Africa.

This is a problem, and a fight, that must be shared by African people

everywhere. In this effort to complete the liberation of Africa

and free Africa from dependency, we must extend the base

of Pan-Africanism into a concept of an African World Union. This should be the

mission of the present generation of Africans. It should also be the legacy

that we leave for generations of Africans still to come.

In the search for our new place in the African sun and in the respectful

commentary of world history, it is necessary that we look at the past in order

to understand the present and probably prophesy the future. There are some

critical questions we need to ask and answer, mainly, Are African people ready

for the twenty-first century? Are we preparing to be free men and women,

masters of our destiny or will we continue in the programmed dependency that

has been our lot for the past 500 years? I maintain that it is the role of

African thinkers, teachers and political leaders to ask the question, How will

my people stay on this earth?

In order to survive, some of us have felt the need to live in a form of sick

fantasy. Are we as a people ready for the consequences and the responsibilities

of being free and self-governing in the next century?

Part of the answer to the question, Are we ready for the twenty- first

century? is the statement: African people must first define themselves. They

must decide who they are and understand their place in the world.

I have often said that history is the clock that people use to find their

political time of day. It is also a compass that they use to locate themselves

on the map of human geography.

We are a world people, a potentially powerful people without power and we need

to know why. We have been a natural attraction for other people. That was the

basis of the crisis in Africa 3000 years ago. This

the basis of the crisis in the African world right now. African people, all

over the world, have answered to too many names that they did not choose for

themselves. In finding yourself you have to find who you are, and what name you

are to be called: (1) Negro; (2) Colored; (3) Black; (4) African; (5)

Arab-African (No); (6) Black-African (No). The question is what people did the

slave ships bring here ?

African People At The Crossroads

When you want to lose a people from history, you first

destroy their self-confidence and historical memory. This is the basis of our

dilemma: Our enemy wants us to forget who we were so we will not know what we

still can be. This statement is really about conflict in culture and

self-confidence. Culture, conflict and self-confidence are reoccurring themes

in our lives and in the lives of all people.

With our people, these themes take on a special meaning. We created the worlds

oldest culture, and we act as if we are not aware of this fact. We have a

conflict within ourselves about how to use culture as an instrument of

liberation. If we had confidence in our culture, the second rate cultures of

other people would not fascinate us.

What we do not seem to know is that our oppressor, who created the crisis, in

most cases is also having a crisis of self-confidence of different nature. The

rulers of the world are in trouble because they cannot continue to rule over

us. They have developed some skill in taking advantage of our crisis, but we

have developed no skill in taking advantage of theirs. We are following a

people who do not know where they are going.

Among other things, whites are turning to African religions because Africa

is the origin of Eastern religions. Europeans are losing confidence in the gods

that they sold to us. European rule over the world has been, and still is, a

con-game. We are its victims and we can now decide the game is over. Today,

many Europeans are turning toward Eastern and African religions and cults,

while more blacks are turning to millionaire gospel peddlers like: Jimmy

Swaggert and Billy Graham, who are racists. We live in a world of fantasy,

searching for someone to love us, when all we need to do is love ourselves. We need

to love ourselves so well that we will begin to make the shoes we wear and the

rest of the clothes we wear. We should love to run the stores in our community,

and we should do so with pride.

According to the Chicago poet, Haki

Madhabuti, We are the only people who turn our children, over to the enemy to be educated. We should

start educating our children ourselves. Powerful people never educate

powerless people in how to take their power away from them. Education, as I

have said before, has but one honorable purpose; that is to train the student

to be a proper handler of power. At first power over himself or herself. Our

communities are small nations under siege. They are about to be taken away from

us because we do not realize that we have no place to go and must now take a

stand.

The Way Out

The answer to the question: Are we ready for the

twenty-first century is both complex and simple.

We need to look back at the early part of the twentieth century in order to

estimate what we might have to do in the early part of the twenty-first century.

Between the United States,

the Caribbean Islands,

South America and Central America,

there are over 200 million African people, not including those who are hiding

the fact. Taking into consideration the newly discovered Africans on the

islands of the Pacific and in other parts of Asia, there

are at least 300 million people of African descent living outside of Africa.

The Africans in Africa number at least 500 million. How

did we get to be called a minority, anyhow? In the next century, there will be

at least a billion African people in the world. We will be the second, if not

the first, largest ethnic group in the world.

How do we deal with that?

We must look into education for nation-management. We cannot leave it to others

to let us know about this. We need to listen to the black men that we have not

listened to very well: Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey.

Pan-Africanism and African world unity is the real answer. The need is not just

to unite against some thingbut to unite for something. When we find ourselves,

we will have to understand the role we as a people have played in history and

still must play. Nation-management is our only hope.

As Professor Willard Johnson of Massachusetts Institute of Technology has said,

We can change the worldif first we change ourselves.

In a nation of immigrants, the black American is really unique. We are the

immigrants who came to the Americas

After the middle of the nineteenth century, black Americans in the United

States were no longer considered to be

African. What to call them has always been a dilemma. W.E.B. DUBOiS reminds us

that we were brought to America

as temporary immigrants, with the assumption that we would eventually be

returned to Africa. He also reminds us that our first

institutions bore the name African, such as The African Methodist Episcopal

Church, and the African Lodge that became, in actuality, the first black

Masonic order established in the United States.

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, we began to refer to ourselves

as colored or negro. However, neither word has any meaning in reference to

the national home base of a people. We did not begin to use the word black

until the middle of the twentieth century, during the period of the Supreme

Courts decision against segregated schools in 1954 and the rise of the Civil

Rights movement after the Montgomery

bus boycott of 1955.

The word African again became part of our conscious speech after the African

Independence Explosion, starting with the independence of Ghana

in 1957. With the rise of the Black Studies concept following the beginning of

the decline of the Civil Rights movement, the word black became more

acceptable to a larger number of Americans of African descent. With the same

consideration being given to the Pan- African concept, the word African once

more became a part of our vocabulary. What the Africans living outside of Africa

began to understand, especially those living in the United

States, is that we are a nation within a

nation still searching for a nationality. Italian- Americans, German-Americans,

Asian-Americans, and other hyphenated Americans do not seem to have any

problems referring to the country and the land of their geography as part of

their heritage.

Some of us are just beginning to be comfortable with the word African.

Numerically, in the United States,

we are more than a nation, although we are sometimes lacking in

nation-consciousness. Professor Ivan Van Sertima has said that we have been

locked in a 500-year room tragically shielded by a curtain marked Slavery.

Our desire to look behind and beyond that curtain is what the concept of Black

Studies was all about. We African people of the world, along with the Chinese,

are the only people who might number a billion people on the face of the earth.

African people are the most dispersed of all of the worlds people. When you

consider the fact that between the Caribbean Islands and the large number of

African people in South America, especially Brazil, which has the largest

number of African people living outside of Africa, there are at least 200

million African people in the Western hemisphere. When you consider the large

number of African people in Asian countries and on the Pacific

Islands, there are more than 100

million African people living in the Eastern hemisphere. This does not include

the 100 million people living in India,

referred to in a recent book as the Black Untouchables.

There is a need now to read or reread Sir Godfrey Higgins book, Anacalypsis,

originally published in 1833, which deals with the dispersion of African people

throughout the world. Our presence and the culture that we have created have

influenced the whole world. Because of racism and the colonization of the

information about history, we are considered strangers among the worlds people

and called many different names in the many places where we live. The name that

is applicable to all of us, wherever we live on this earth, is African.

Whats in a name? Shakespeare said, in effect, A rose by any other name is

just as sweet. That is all right when you are dealing with roses, but when you

deal with people you have to be more precise.

Jesse Jacksons announcement that black people in the United

States should be called Africans caused me

to sigh with some boredom and ask, What else is new? I, personally like Jesse

Jackson and have no fight with him in this regard. His remarks and the numerous

radio and TV talk shows that recently discussed the name prove to me that the

public pays more attention to politicians than they do to scholars. Since the

mass forced emigration of Africans outside of Africa in the fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries, during the slave trade, which contributed to the economic

recovery of Europe after the Middle Ages, African people in one way or the other

have been searching for their African selves. What we need to learn here is

that in the European conquest and colonization of most of the non-European

world, they also colonized information about the world.

They knew then what most of us dont seem to know now: You cannot successfully

oppress a conscious historical people.

Once a people knows who they are, they will also know what they have to do

about their condition. To make a people almost assume that oppression is their

natural lot, you have to remove from them the respectful commentary of their

history and make them dependent on the history of their conquerors. To infer

that a people have no history is also to infer that they have no humanity that

you are willing to recognize. African people the world over need a definition

of history that can be operational in different places at different times and

operational everywhere African people live. Because we are the most dispersed

people on the face of the earth, our operational definition of history must be

universal in scope, applicable to people in general, and to African people

specifically.

This is my definition: I repeat, "history is a clock that people use to

tell their political and cultural time of day. It is also a compass that people

use to find themselves on the map of human geography. The role of history is to

tell a people what they have been and where they have been, what they are and

where they are."

The most important role that history plays is telling a people where they still

must go and what they still must be. No people can move into the mainstream of

history and be respected when they answer to an ethnic name not of their

choosing and worship a God-concept not of their choosing. All people develop

within a culture container that includes their geographical background, their

religion, and their method of surviving in their original habitat. When you

take a people out of the cultural surroundings in which they originally

developed, you take away part of their humanity. African people living outside

of Africa are so obsessed with surviving under

conditions that they did not create that they often lack a universal view of

their condition and how it started.

The writer, Lerone Bennett, Jr., has said, We have been named, we should now

become namers. In the process of reconsidering ourselves and our role in

world history, our initial assignment is to find the proper name for ourselves.

The name colored means nothing because all people are colored, one way or

another. The name negro should mean nothing to us because there is no such

race of people or person. Some Spaniard or Portuguese took a descriptive

adjective and made a noun out of it. We as a people are neither a noun nor an

adjective. Those who responded, pro or con, to Jesse Jacksons suggestion that

we use the name African also clearly indicated that they had not read any of

the reasonably large body of literature on the subject. Among some of our

scholars this debate has been going on for almost 200 years with small audiences

that obviously did not understand the nature of the debate. There are times

that when a people answer to a name that they did not choose for themselves

they fall into a condition that they also did not choose. If you answer to the

name dog, in some ways you will become a dog.

Over 100 years before the abolition of slavery, our scholars were addressing

themselves to this situation. They were close enough to the name African to

have no compunction about using it. This is a late seventeenth and early twentieth

century debate. The Brazilian abolitionists of African descent argued among

themselves whether they were Brazilians or Brazilian-Africans. Paul Cuffe, the

first black American sea captain was very clear about his African name and his

African heritage. In the non-fictional historical writings of our first

novelist, William Wells Brown, the word Ethiopian was often used synonymously

with African and black as though they were interchangeable. I now refer to

the book, Search for a Place, that contains Martin Delanys report on the NigerNew

England blacks emerged, they mainly used the name African in

their writings and references to African people.

When the Barbadian, Prince Hall, founded the first black Masonic order,

he called it the African Lodge. When Richard Allen and other black religious

dissidents founded the independent black church, they called this church The

African Methodist Episcopal Church. Our first stage comedians were often

referred to as the African clowns or the Ethiopian rascals.

Edward Wilmot Blyden, in his famous inaugural address at Liberia

College, in 1881, spoke of the

images about ourselves that were created by other peoples interpretation of

what we are and what we should be. Dr. Blyden said in his address: We shall be

obliged to work for many years to come without the sympathy or understanding we

need to have. He also said that we as a people are in revolt against the

descriptions of African people in travelogues, textbooks and in journals by

missionaries and mercenaries. He further explained that we often strive to be

those things most unlike ourselves, feeding grist into other peoples mills

instead of our own. He concludes, Nothing comes out except what has been put

in and that, then, is our great sorrow. Professor Blyden continued this

emphasis in other works like, On African Customs, and his greatest and

best-known work, Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race.

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, when George Washington Williams

was writing the first formal history of the African people in the United

States, The History of the Negro Race in the

United States,

he introduced the book with an argument he seemed to be having with himself

about the word African as opposed to negro. He must have lost the debate

with himself, because in spite of favoring the word African he used negro

throughout the two-volume work.

The greatest intellect, in my opinion, that we have produced outside of Africa

emerged in the closing years of the nineteenth century. His name is W.E.B.

DUBOiS. His book, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United

States was published by Harvard University

Press. Booker T. Washington and his educational theory of self-reliance emerged

during the same period. These two minds, using different words and methods,

guided the Africans in the United States

into the twentieth century. We were now using the word negro or colored in

order to distinguish ourselves from the Africans living in Africa

and those living outside of Africa. However, the word

negro was not extensively used in the Caribbean

Islands nor in South

America. In his famous appeal of 1829, David Walker had used the

word colored. In our publications and documents the name negro became our

new mark of identity, as reflected in publications like the Negro Year Book,

edited at Tuskegee Institute by Monroe Work. In 1915, when Carter G. Woodson

founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and later the

Negro History Bulletin, Africans in the United

States were more or less settled on the word

negro.

The literary movement of the 1920s, sometimes called The Negro Renaissance or

the Harlem Renaissance, had its emphasis in two different places: one in the

reclaiming of the African past and the other in surviving the conditions that

African people had to live under in the United

States, the Caribbean

Islands, and in South

America. Interests merged at this point and some intellectuals

began to think of a Pan-African movement that would encompass all the African

people of the world. In 1927 the Jamaican, Raphael Powell, seriously questioned the use

of the work negro in his book, The Human Side of a People and the Right Name.

Mr. Powell dedicated his book to the human race, especially to those who

have been taught to believe that they are other than what they are and to those

who will think with a mind of reason, logic and common sense ....

Mr. Powells opinion was that Ethiopian was co-ordinate with Mongolian,

Malay, Indian and Caucasian as ethnic labels and that the word negro was not

only a superfluous term but one that carried with it a connotation of contempt,

opprobrium and inferiority. Mr. Powell further stated, Biblical literature

has not a single reference to black men as negroes although black men figure

repeatedly in Bible lore. He said, In Africa, as elsewhere, neither color nor

language can serve as criteria of the homogeneity of race. From Willis

Huggins Forward to this book, I extract the following quotes:

If not strange, it is at least unique, that American-born Africans became

negroes in common parlance, while American-born Europeans, or Asiatics,

remain Italians, Poles, Koreans, Japanese or Tibetans.

Although it is too late for peoples of African descent to trace their lineage

to any particular African tribe, yet for all that, they remain Africans.

What is needed in this matter is new education; unbiased instruction which

should lead to the recognition of particular African peoples for what they are,

i.e., Basutos, Buandas, Nubiaris, Senegalese.

Dr. Huggins summation of Raphael Powells finding is that this will require

the preparation of simple texts in ethnology and anthropology by experts and

there placed in the common schools and used in lecture forums. Mr. Powell

continued his inquiry in other books, No Black-White Church and The Common

Sense Conception of the Race Problem. Dr. Huggins further stated that, Mr.

Powell is on the right track in running down the word, negro for he sees that

just as the word Aryan has come to plague Western Europe today; he predicts

that the word negro will rise in the future as a plague to America and the

Western world.

Mr. Powells book is the first extensive investigation into the semantics of

race as it refers to African people. In the early 1960s

Harlem bookstore owner and political activist, Richard

B. Moore, formed a committee to tell the truth about the word negro. Mr.

Moore and his committee were of the opinion that the word needed to be dropped

from our vocabulary as having no relevance to the identification of a people.

In his book, The Name Negro, Its Origin and Evil Use, he said, Slaves and dogs

are named by their masters. Free men name themselves. Mr. Moore further stated

that the proper name of any people must relate to land, history and culture. He

emphasized that black tells you how you look, but it does not tell you what you

are. Africa is the home of a variety of people, of many

shades and colors, but mainly they are black. Any person in Africa,

he further stated, who cannot be referred to as an African, is either an

invader or the descendant of an invader.

No disrespect for Jesse Jackson is intended, but I am of the opinion that he

has not read one word of this literature of definition that black scholars have

been creating for over 100 years.

In the 1968 challenge of black scholars to the African Studies Association,

their main disagreement with the white-dominated organization was over the

definition of African people in world history. Their explanation for the

formation of a new organization, the African Heritage Studies Association, is

detailed in their objectives as follows:

INTRODUCTION:

The African Heritage Studies Association (ASHA) is an association of scholars

of African descent, dedicated to the preservation, interpretation and academic

presentation of the historical and cultural heritage of African peoples both on

the ancestral soil of Africa and in Diaspora in the Americas and throughout the

world.

Aims and Objectives:

1. EDUCATION:

a. Reconstruction of African history and cultural studies along Afro-centric

lines while effecting an intellectual union among black scholars the world over.

b. Acting as a clearing house of information in the establishment and

evaluation of a more realistic African Program.

c. Presenting papers at seminars and symposia where any aspect of the life and

culture of the African peoples are discussed.

d. Relating, interpreting and disseminating African materials for black

education at all levels and the community at large.

2. International:

a. To reach African countries in order to facilitate greater communication and

interaction between Africans and Africans in the Americas.

b. To assume leadership in the orientation of African students in the United

States and orientation of African- Americans

in Africa (establish contacts).

To establish an Information Committee on African and American relations whose

function it will be to research and disseminate to the membership information

on all aspects of American relations with respect to African peoples.

3. DOMESTIC:

a. To relate to those organizations that are predominantly involved in and

influence the education of black people.

b. To solicit their influence and affluence in the promotion of Black Studies

and in the execution of ASHA pro grams and projects.

c. To arouse social consciousness and awareness of these groups.

d. To encourage their financial contribution to Black schools with programs

involving the study of African peoples.

BLACK STUDENTS AND SCHOLARS:

a. To encourage and support students who wish to major in the study of African

peoples.

b. To encourage black students to relate to the study of the heritage of

African people, and to acquire the ranges of skills for the production and

development of African peoples.

c. To encourage attendance and participation including the reading of papers at

meetings dealing with the study of African life and history so that the African

perspective is represented.

d. To ask all black students and scholars to rally around ASHA to build it up

as a study organization for the

reconstruction of our history and culture.

BLACK COMMUNITIES:

a. To seek to aid black scholars who need financial support for their community

projects or academic research.

b. To edit a newsletter or journal through which ASHA activities will be known.

In the new interest in Pan-Africanism that is gaining momentum throughout the

African world, the intent of the Africans is not only to change their

definition in world history but to change their direction. Theirs is a hope

that Pan-Africanism will spread beyond its narrow intellectual base to become

the motivation for an African World Union. This will begin when we recognize

that we are not colored, negro, or black. We are an African people

wherever we are on the face of the earth.

African people will have to take a three-way look at themselves, using the past

to evaluate the present and using the present to prophesy the future. In our

long journey on this earth, we have had few friends, if any. All non-Africans

who have come among us or been associated with us have clearly shown that they

would betray us any time it was in their self-interest. We have never made good

alliances with other people. Properly counted, Africans may number a billion

people on the face of the earth. With that many Africans in the world, and with

some political astuteness, we are in a position to make either alliances that

are to our benefit or none at all. We know that the most important alliance we

need to make is among ourselves.

To be sufficiently argumentative on the subject of black-white alliances, I

would have to speak for a week, and I would still barely exhaust the subject:

If there is one thing that can be said about black people that has caused a lot

of pain, and yet is historically true, it is that politically we are one of the

most naive of people. We have been taken in by practically everything and

everybody that has come to us. I think this taking in, this betrayal, has

something to do with both our weaknesses and our strengths. If you find the

strengths of a people, you will find their weaknesses, because the two are

closely related.

In the first place, we have been an extremely humane people. We have been

hospitable to strangers, and nearly always to the wrong strangers. Almost all

of our relationships with non-African people began with gestures of friendship.

More than anyone else in the world, we have repeatedly invited our future

conquerors to dinner. There is a need to look at black-white alliances going

back 2,500 years.

I think .that the nature of our betrayal by people who come among us, who

solicit our help and get it tells us something that is quite frightening, i.e.,

we are a totally un-obligated people. We dont owe Christianity anything

because we created the religion. The Europeans bought it, reshaped it, sold it

back to us and used it as a basis for the slave trade. We created Islam; then

the Arabs, after years of fruitful partnership with us, turned on us and used

Islam to justify their slave trade. We created the concept called socialism: An

African king 1300 years before the birth of Christ was preaching the same thing

that Karl Marx thought he invented. When the newly-found socialism used us, it

turned on us. In looking at alliances, were taking a global view of the

African and his humanity and the manifestations of his humanity in relationship

to people in other parts of the world.

At one point, there was a disruption within Africa

itself. The African Cushites invaded Egypt.

The people of the Middle East (again, this tells you something about how we

might miss certain points) were buying iron from a city called Meroe in Cush,

from which they made iron-tipped weapons, while the magnificent army of Cush

was using bronze-tipped weapons; bronze is softer than iron. With the iron

bought from the Africans, they could drive Africans out of the Middle

East and begin the decline of Egypt.

Once again Africans had naively trusted an ally.

You will find this pattern consistent from the Shepherd King alliance to the

alliance of American blacks with the American Communist Party. Africans are

always a junior partner. If the alliance can be broken without your consent,

then it is not an alliance. You are a servant of it instead of being a partner

of it. If it is a genuine alliance and a genuine friendship, then collectively

both of you decide how it should go and how it should not go. Why are so many